Home » Posts tagged 'fencing courtesy'

Tag Archives: fencing courtesy

Fencing Quotations

Useful advice and commentary, by category, for swordsmen and swordswomen. I’ve collected these over almost fifty years from a variety of sources, ranging from books published over several centuries to fencing masters and even to my own observations.

Some of these quotations are repeated in my post, Fencing Salles & Fencing Commandments, along with other advice and commentary. Please note that the list below is not complete, and never can be. I will, however, update it as convenient.

Except where noted, the English translations from the original French are mine.

A long detailed list of fencing books can be found here.

On the Virtues of Fencing

“And moreover, the exercifing of weapons putteth away aches, griefes, and difeafes, it increafeth ftrength, and fharpneth the wits, giuith a perfect iudgement, it expelleth melancholy, cholericke and euill conceits, it keepeth a man in breath, perfect health, and long life. It is vnto him that hath the perfection thereof, a moft friendly and comfortable companion when he is alone, hauing but only his weapon about him, it putteth him out of all feare, & in the warres and places of moft danger it maketh him bold, hardie, and valiant.”

—George Silver, Paradoxes of Defence, 1599

“If you master the principles of sword-fencing, when you freely beat one man, you beat any man in the world. The spirit of defeating a man is the same as for ten million men.”

—Musashi Miyamoto, Go Rin No Sho (A Book of Five Rings), 1645. Musashi, Japan’s kensei or “sword saint,” fought and won more than sixty duels before retiring as a hermit to write his famous masterpiece on swordplay and strategy. Of course, what readers often miss is the implication: that you don’t have to have a brilliant understanding of the “Way” in order to fence well—Musashi himself admits that he didn’t understand the true Way until after he had fought all of his duels—but certainly it would help.

And in the West, a similar sentiment:

“J’asseureray que celui qui est instruit dans les armes, ayant du cœur, réussira contre cent mal adroits; j’entends l’un après l’autre, nullus Hercules contra duos.”

“I will assure that he who is instructed in arms, having a stout heart, will succeed against one hundred clumsy swordsmen; [yet] I hear often that there is no Hercules against two [other swordsmen].”

—André Wernesson, sieur de Liancour, Le maistre d’armes: ou, L’exercice de l’epée seule, dans sa perfection, 1686. My translation. The admonition that no one is a Hercules against two adversaries is often written as “No Hercules against the multitude.”

And yet…

“[B]ecause, when a vigorous and brisk Officer, hath perhaps Disabled or run one Enemy thorow, and is actually commanding [grappled with] of another; there steps in a Third, who endeavours to knock him on the head, or Cleave him down; for, Ne Hercules quidem contra multos.”

—Sir William Hope, A New, Short, and Easy Method of Fencing, 1714. Here Hope takes the opposite–and certainly more correct view, swashbuckling films notwithstanding–view that it is difficult, if not impossible or at least highly unlikely, to succeed against multiple adversaries attacking at once. Unlike in Hollywood where enemies are trained to attack one-at-a-time per the script, multiple adversaries tend to attack simultaneously. Hope suggests that the hanging guard might defend against two adversaries while a thick leather gauntlet in the non-dominant hand might defend against a third. But with offense comes at least one opening for the several adversaries…

“When you count all the benefits of swordsmanship, there are so many, encompassing the virtues of heaven and earth.”

—Yagyu Muneyoshi, 17th century, translated by Hiroaki Sato.

“So doeth the Art of Fencing teach us to defend our Bodies, from the Assaults and Attaques of all Adversaries, whether Artists or not, who in respect of the cruel designe they have against our Bodies, may in some sense be accounted Devils, it also teacheth us not to be deceived by the fallacious Quirks and Tricks of Artists when we are engaged with the which do represent the cunning subtile Allurements of the World.”

“[Y]et all Gentlemen should practice it, & have an esteem for it, if it were for no other reason but this, that it is a most pleasant divertissement, and an Innocent, Healthful, and Manly Recreation and Exercise for the Body, and although a Man could reap no Advantage by it for the Defence of his Body; yet that its very keeping a Mans joynts and members nimble and cleaver [clever], and in a ready trime [trim], as it were, for any other Divertisement or Exercise, as Tenice, Dancing, Riding, &e. should make it Esteemed and Practised by all who are above the rank of Clowns.”

—Sir William Hope, The Sword-Man’s Vade-Mecum, 1694

“Nothing can give a greater Lusture and Enoblement to the most Excellent and Bravest Persons, than an absolute and perfect Qualification in the true Knowledge and Skill in Weapons.”

—Zachary Wylde, The English Master of Defence, 1711

“Indeed I am perfectly of opinion, which is corroborated by numberless persons who have experienced the utility of fencing, that for the navy it should be considered as one of the most essential branches of a nautical education, and ought to be encouraged by Captains and Commanders as much as possible. The ship’s company should, every one of them, be compelled to understand the use of the sword familiarly, previously to their going abroad, and should continue practising it at all times on board; for they have, if possible, even more occasion for fencing than the army, because, in general, they are more frequently at close quarters with the enemy than the military are.”

—Joseph Roland, The Amateur of Fencing, 1809

“Glancing fearfully about, I took up the weapon, finding it play very light in my grasp for all its size; and having wielded it, I held it that the moonbeams made a glitter on the long, broad blade. Now as I stood, watching this deadly sparkle, I trembled no longer, my side fears were forgotten, a new strength nerved me and I raised my head, teeth clenched in sudden purpose so desperate bold indeed as filled me with marvelous astonishment at myself; and all this (as I do think) by mere feel of this glittering sword.”

“There remains then always your sword, friend Adam; with this you may win the fame, the fortune—or the grave so honourable. Ha, it is true, when all other fails, there remains always—the sword!”

—Jeffery Farnol, Over the Hills, 1930

“I would consider Laci Nedeczky as a role model, he is the type who has unfortunately already died out in the great scramble, where only business and money are important, and altruism is already on the wane…”

“Nedeczky Lacit példaképnek állítanám, ő az a típus, aki sajnos kipusztult már a nagy tülekedésben, ahol csak az üzlet, a pénz a fontos, és az önzetlenség már szűnőben van…”

—Dr. Francis Zold (Ferenc Zold) commenting on the 90th birthday of László Nedeczky in 2003. Fencing is often believed to instill great virtues, or at least it can. However, many observers have noticed a great diminution in the number of noble, altruistic fencers, alongside a diminution in the number of swashbuckling fencers and masters: often they were one and the same. Quoted in an article by Kö András.

Defining Fencing & Swordplay

“Fencing is neither art nor science. Fencing is fencing!”

—Dr. Francis Zold, personal communication, 1977

“Fencing—is speed!”

Eugenio Pini, quoted in László Szabó, Fencing and the Master, 1977

“The use of arms doth much differ in these times. I hear now the single rapier is altogether in use: when I was young, the rapier and dagger. And I cannot understand, seeing God hath given a man two hands, why he should not use them both for his defence.”

—William Higford, Institutions: Or, Advice to His Grandson, 1658

Mr. Higford makes an excellent point: the reality of real combat with thrusting swords is that the unarmed hand must come into play, if only in opposition in order to prevent angulations and other continuations of attacks and ripostes, not to mention to use in extremis as a parry or by grasping to defend oneself. Only in highly regulated formal duels—those of the 19th and early 20th century epee de combat, for example—may this practice be proscribed (and, of course, in sport fencing). See also Sir Wm. Hope immediately below.

“That if a good and dexterous Sword-man have no other design but Defence of his own Person, and not the Destruction of his Adversary’s also, that then his Sword alone, assisted by a judicious Breaking of Measure [retreating], is…sufficient to defend him: But again, if he design to Offend [attack] as well as Defend, then there is an absolute Necessity to make use of his left Hand for his Assistance; otherwise his Adversary, continually redoubling his Thrusts irregularly and with Vigour upon him, he shall never almost have the Opportunity of Thrusting, his Sword being in a manner wholly take up with the Parade, by endeavoring to make good his own Defence…”

“There is a vast difference, betwixt assaulting in a School with Blunts, for a Man’s Diversion, and engaging in the Fields with Sharps, for a Man’s Life; and whatever latitude a Man may take in the one, to show his Address and Dexterity, yet he ought to go a little more warily, and securely to Work, when he is concerned in the other: For in assaulting with Fleurets [foils], a Man may venture upon many difficult and nice Lessons, wherein if he fail, he runs no great Risque, and if they take not at one time, they many succeed at another: But with Sharps, the more plain and simple his Lessons of Pursuit [attack] are, so much the more secure is his Person; whereas, by venturing upon variety of difficult Lessons, he very much exposes himself, even to the hazarding of his Life, by his Adversary’s taking of Time, and endeavouring to Contretemps [an attack into an attack or a simultaneous attack, often resulting in a double touch], which are not so easily effectuat [sic, “effectuated,” i.e., “executed”] against a plain and secure Pursuit [attack].”

“[T]hat it clearly appears, that what goes under the Name of Graceful Fencing, is for no other use, but only for such, as, for Divertisement, counterfit a Fight with Blunts, who only Assault in the Schools with Foils.”

—Sir William Hope, A New, Short, and Easy Method, 1714

“And, though none might suspect it from his clumsy bearing, he is a noted swordsman.”

—John Dickson Carr, Most Secret, 1964. Many excellent fencers appear clumsy or ungraceful, or lack classical form.

“I enjoyed swordsmanship more than anything because is was beautiful. I thought it was a wonderful exercise, a great sport. But I would not put it under the category of sport; I would put it under the category of the arts. I think it’s tremendously skillful and very beautiful.”

—Basil Rathbone, interviewed by Russ Jones for Flashback magazine, June 1972. Modern “Olympic” fencing might be much improved if more fencers and their teachers took this attitude. Rathbone was without doubt the best of the non-competitive Hollywood fencers.

“Briefly, our method could be expressed in this sentence: ‘The best parry is the blow.'”

—Luigi Barbasetti, The Art of the Sabre and the Épée, 1936.

“The most efficacious means of fighting are offensive actions—above all attacks. In all weapons the majority of fencers score the largest amount of hits by attacks…”

—Zbigniew Czajkowski, Understanding Fencing, 2005

However, according to many of the French and derivative schools, old and new, note the following two quotations…

“…but also procures to himself the advantage of playing from the Risposte, which of all Methods of Fencing is the most commendable, and safest, but then, as I have said, it is only to such as are Masters of the Parade; which is a quality rare enough to be found, even amongst the greatest Sword-men.”

—Sir William Hope, A New, Short, and Easy Method of Fencing, 1714. In other words, the method of relying foremost on the riposte is ideal—but only if you have the rare ability of mastering it. My own preference is for a patiently aggressive balance of offense and defense, added to judicious use of second intention actions which provide the opportunity to both attack and riposte. See especially the quotes on patience below.

“It is more dangerous to attack than to parry. Instead of waiting you let yourself go. And the great difficulty is to know how to let yourself go far enough without going to far.”

—Baron de Bazancourt, Secrets of the Sword, 1900 (English translation by C. F. Clay of the original 1862 French edition.)

“Dans les salles on discute la valeur des méthodes; qu’il s’agisse de radaellistes (école réformée d’Italie) de méridionaux (obscurantists de l’antique école napolitaine) ou de pinistes, on donne á notre école cet avatage de ne pas exiger une musculature extraordinaire: un tireur italien doit être un hercule, un tireur français peut être…une femme.”

“In the salles the value of the methods is discussed; whether they are Radaellists (the reformed school of Italy [named for the famous Radaelli]), or Southerners (obscurantists of the ancient Neapolitan school), or Pinists [named for the famous Pini], we argue that our school has the advantage of not requiring extraordinary musculature: an Italian fencer must be a Hercules, a French fencer can be…a woman.”

—”Rapière,” “L’Illustration,” 28 May 1892

“La spada è acuta, pungente, affilata, forbita, fatale, formidabile, lucida, nuda, fina, forte, ben temprata, nobile, perfetta.“

“The epee is pointed, biting, sharp, forbidding, fatal, formidable, shiny, naked, fine, strong, well tempered, noble, perfect.”

—Agesilao Greco, La Spada e la sua Disciplina d’Arte, 1912

“The genius of the French school is, of course, opportunist. In theory, every move of the adversary is acted on as it is made. The Italian fencer relies more on deductions from what has passed, and on premeditated schemes of attack and defence. Hence the diversity of the spirit in which the systems of opposition are conceived.”

“For the practical realist there is the duelling sword [the epee]; for the stylist there is the foil; for the imaginative and the artistic there is the saber. But some sense of reality, some sense of style, and some sense of artistry is essential to the practice of any one of the three weapons.”

—Percy E. Nobbs, Fencing Tactics, 1936. One might add the Hungarian school to his description of the Italian, given its heavy Italian influence and similar attitude toward tactics.

“La scherma, come l’aritmetica, no sopporta opinioni; essa è un fatto governato da leggi sicure, fisse, esperimentate, le quali se pure tollrano qualche leggera variante all loro forma esteriore, sogliono rimanere integre nella sostanza, perchè conducono sempre allo stesso, allo identico resultato. Insomma: la scherma nostra è come una bella signora la quale muti d’abito: la persona resta sempre la medesima.”

“Fencing, like arithmetic, does not tolerate opinions; it is a fact governed by sure, fixed, tested laws, which, even if they tolerate some slight variation to their external form, usually remain intact in substance, because they always lead to the same, identical result. In short: our fencing is like a beautiful lady who changes her dress: the person always remains the same.”

Eugenio Pini, Tratto Pratico e Teorico Sulla Scherma di Spada, 1904

“L’escrime est une science expérimentale, soumise à des lois immuables comme las physique et la chemie. Chaque movement y a son importance, sa signification, et on peut en verifier les consequences, les avantages et les inconvénients. L’escrime est une art; certaines natures, particulièrement douées, y sont parfois prepares, predestines; mais il faut s’appliquer assidûment pour atteindre à la perfection.”

“Fencing is an experimental science, which operates under immutable laws just as do physics and chemistry. Each movement has its importance, its significance, and one can verify the consequences, advantages, and disadvantages. Fencing is an art; certain natures, particularly gifted, are sometimes prepared, predestined, but it is necessary to apply oneself diligently to achieve perfection.”

—Dr. Achille Edom, L’Escrime, le Duel & l’Épée, 1908. My translation.

“L’art des armes ne consiste pas, contrairement à ce qu’a dit Molière, “à donner et à ne pas recevoir”; mais à ne pas recevoir d’abord et à donner ensuite, si l’on peut.”

“The art of arms consists not, contrary to what Molière said, ‘to give and not to receive,’ but at the outset to not receive and to give subsequently, if one can.”

“Il ne doit y avoir qu’une école d’escrime, celle qui prepare le tireur aussi bien pour l’assaut public que pour le terrain. En un mot, j’estime que l’escrime doit rester un art, mais il ne faut pas qu’elle demeure sans utilité pratique.”

“There must not be but one school of fencing, that which prepares the swordsman as well for the public assault [sport] as for the terrain [duel]. In a word, I deem that fencing must remain as an art, but it must not remain without practical use.”

— Anthime Spinnewyn, L’Escrime à l’épée, 1898. My translation.

“[I]l y a deux escrimes, l’escrime du fleuret et l’escrime de l’épée, l’escrime de la salle et l’escrime du terrain.”

[T]here are two forms of fencing, foil fencing and epee fencing, the swordplay of the club [sport fencing] and the swordplay of the [dueling] ground.

“N’est-ce pas là une indication de plus qu’il y a deux escrimes, l’escrime du fleuret, sport admirable, mais exercice de convention, et l’escrime à l’épée, méthode de combat?”

“Isn’t this more of an indication that there are two forms of fencing [with thrusting weapons], foil fencing, an admirable sport, but an exercise of convention, and epee fencing, a method of combat?”

—Arthur Ranc in the preface to Le Jeu de l’épée by Jules Jacob, 1887. My translation.

“Jusqu’à ce jour l’Italie a représenté l’école romantique; la France, l’école classique.”

“Up to this day Italy has represented the romantic shool; France, the classical school.”

—Aurélien Scholl, in the preface to Deux Écoles d’armes: L’escrime et le duel en Italie et en France by Daniel Cloutier, 1896. My translation.

“Gallant bearing, disdainful valour, all that is very well in its way, ‘but the thing, Sir, is to hit your man without being hit yourself.’ That is the wisdom of ages.”

—Egerton Castle, “Swordsmanship Considered Historically and as a Sport,” 1903.

“But delightful as good foil-play is, both to performers and lookers-on, it is neither the real sword-fight nor even a reasonably complete preparation for it.”

—Charles Newton-Robinson in “The Revival of the Small-Sword,” 1905, in The Living Age.

“‘Henry Durie,’ said the Master, ‘Two words before I begin. You are a fencer, you can hold a foil; you little know what a change it makes to hold a sword!'”

—Robert Louis Stevenson, The Master of Ballantrae, 1889

De Meuse. — “L’assaut à l’épée de combat doit être l’image la plus complete possible du duel. Or, dans un duel, on ne donne jamais qu’un seul coup d’épée.”

Berger. — “Quelquefois deux et trois. Après une petite blessure on ne s’arrête pas.”

De Meuse. — “The dueling sword bout ought to be the closest image possible of the duel. However, in a duel, there is never only a single epee thrust [wound].”

Berger. — “Sometimes two and three. After a small wound one does not stop.”

—From the Troisième Congrès Internationale d’Escrime, 1908. The Congress was called to determine rules for fencing as sport. Unfortunately, the argument of M. De Meuse failed due to the opposition of foilists who dominated the Congress. They believed epee—the “modern school”—was largely degenerate as a separate weapon and that no special preparation was necessary. These gentlemen had already long since accepted the argument for sport fencing, based on foil fencing as an exercise in technique (much of it useless in actual combat), as something beyond combat and unnecessary to emulate it. In fact, foil had long been proved inadequate for actual combat. See the next quotation.

Renard. — “Nous avons tort de nous mettre dans l’idée que l’assaut est l’image du combat. Je fais de l’escrime comme sport et non pour me batter (marques generals d’approbation) et, autant que possible, pour faire quelque chose de bien. Il ne s’agit pas seulement de toucher.”

Renard. — “We are wrong to put forth the idea that the assault is the image of combat. I fence for sport and not to get battered (general marks of approval [from others]) and, whenever possible, to do something to benefit myself. Fencing is not only about getting the touch.”

—From the Troisième Congrès Internationale d’Escrime, 1908. M. Renard is correct that no bout or assault can be the image of actual combat; no training or practice can. However, from this point forward the idea of all fencing as entirely a sport pastime began to take root and was the death knell of sport fencing as the emulation of actual combat as opposed to sport fencing as pure sport. It’s only grown worse a century later, with foil and saber now entirely artificial. Epee too has it’s artificialities–all forms of swordplay do–but it remains far closer to actual combat than foil or saber, notwithstanding that in many epee exchanges both fencers are hit, even if only one touch is counted. My translation.

“In competition many irregularities occur in connection with the attack. More and more competitors abuse and exploit the incorrect attitude of the judges, who qualify as an attack every advance of the fencer done with invitation or blade lowered, that is, without a threat, although with great speed. Their judgement goes against the fencer who keeps distance to avoid a fleche, although he begins the actual attack with the threat of his weapon. This decision releases a very dangerous, evil “spirit from the bottle”, because–on the basis of the “end justifies the means” principle–more and more competitors depart from the correct, learnt path and abuse the situation. This endangers the entire foundations of fencing, especially of sabre, which rests on realistic conventions.”

“Education, persuasion and the setting of examples and even severe lessons must be used to put an end once and for all to these deviations which threaten the existence of fencing.”

–László Szabó, Fencing and the Master, 1977

The spirit and deviations are unfortunately, and almost unconscionably, long since out of the bottle, and have turned foil and saber into a mere game of tag, and even epee too. The solution is to enforce the convention of legitimate threats with the blade in foil and saber (as opposed to the ludicrous sophistry that substitutes today, permitting attacks in invitation aka “bent arm”), and in epee to lengthen the time within which a double touch may be made, the last of which would force epeeists to focus once again on the ideal of hitting and, importantly, not getting hit.

“The answer is easy. The great art of swordsmanship consists in laying successful snares, such as making your opponent expect the attack exactly where it is not intended. To deceive his expectations, to break up what he combines, to disappoint his plans, and to narrow his action; to dominate his movements, to paralyse his thoughts, represent the art, the science, the skill, and the power of your perfect swordsman…”

—Sir Richard Burton, The Sentiment of the Sword, 1911. Burton was a swordsman, explorer, linguist, scholar, spy, and translator of The Arabian Nights. He was the first non-Muslim to make the Hajj to Mecca, doing so in disguise. As a swordsman he was known as a fierce fighter, with numerous combats in the field.

“C’est une mine si féconde que cette lutte d’adresse, d’habileté, de science, de coup d’œil, d’énergie, de jugement, où toutes les facultés intellectuelles et physiques s’emploient à la fois et se viennent mutuellement en aide.”

“And after all the art of fence does furnish a most interesting fund of conversation—the art of skillful fighting at close quarters, which implies a knowledge of theory combined with a trained power of execution, which taxes eye and hand, vigour and judgment, and brings into play every faculty of mind and body, each doing its part, and each in turn supplementing and reinforcing the other.”

—Baron César de Bazancourt, Les Secrets de l’Épée, 1862. The translation is from the English edition, Secrets of the Sword, 1900, translated by C. F. Clay.

“[Early epeeists] were realists who preferred the romantic to the classic.”

—R. A. Lidstone, Fencing: A Practical Treatise on Foil, Épée, Sabre, 1952. Ever have I been a romantic realist.

“The real fun of fencing is in working out one’s own ruses: sometimes by inspiration on the spur of the moment in a hotly contested bout; and sometimes at leisure, in the watches of the night, for the discomfiture of some difficult opponent who has had the better of it during the day.”

“After a friendly bout is over one carries away the recollection of a few good things well done. It is easy, often too easy, to forget one’s discomfitures. Incidentally, both fencers have revealed their characters to one another, as well as their physical abilities and mental powers. To know is to understand; thus friendships are made.”

“The essence of the game [looseplay, free fencing] is to interest, not to overpower, one’s adversary, and to outwit with a well executed and theoretically fatal cut or thrust. Then, there is a good laugh; whether at one’s own expense or at that of one’s adversary, does not matter. It is by finding out how a hit was made, as much as by trying to make hits, that one learns what fencing means.”

—Percy E. Nobbs, Fencing Tactics, 1936.

“Not so, Anthony, my faith—no! Your murdering tool is cowardly pistol or blundering musketoon whereby Brutish Ignorance may slaughter Learned Valour and from safe distance. But, as Mind is greater than mere Body so is the rapier greater than any other weapon, and its manage an exact science calling not only for the strict accordance of hand, eye and foot, but for an alertness o’ the mind also.”

—Jeffery Farnol, Adam Penfeather, Buccaneer, 1940. Farnol was a fencer and his descriptions of swordplay are accurate.

MAÎTRE D’ARMES: …tous le secret des armes ne consiste qu’en deux choses: à donner et à ne point recevoir; et, comme je vous fis voir l’autre jour par raison demonstrative, il est impossible que vous receviez, si vous savez détourner l’épée de votre ennemi de la ligne de votre corps; ce qui ne dépend seulement que d’un petit mouvement de poignet, ou en dedans or dehors.

JOURDAIN: De cette façon donc, un homme, sans avoir du coeur, est sûr de tuer son homme et de n’être point tué?

MAÎTRE D’ARMES: Sans doute.

MASTER OF ARMS: …the entire secret of arms consists but in two things: to give and not to receive; and, as I demonstrated to you the other day, it is impossible that you will receive, if you have turned your enemy’s sword from the line of your body; and this depends only on a small movement of the wrist, either inside or outside.

JOURDAIN: In this fashion, then, a man, with no courage, is sure to kill his man and not be killed?

MASTER OF ARMS: Without doubt.

—Molière [Jean Baptiste Poquelin], Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme, 1673. One of France’s most famous playwrights, Molière is poking fun at both the bourgeois and at anyone gullible enough to believe that swordplay is a simple matter.

“…because whoever will be but at the Trouble to visit the Fencing-schools, shall scarcely see one Assault of ten, made either be Artists against Artists, or Artists against Ignorants, but what is so Composed and made up of Contre-temps [double touches resulting from an attack into an attack, or from simultaneous attacks], that one would think the greatest Art they learn, and aime at, is to strive who shall Contre-temps oftnest…”

—Sir William Hope, The Sword-Man’s Vade-Mecum, 1694. True then, true later, true today in all forms of swordplay. Notwithstanding modern idealistic classical and historical fencers who believe, via an imagined nostalgia, that the swordplay of past eras was more correct and useful for the encounters with real blades, Hope, not to mention close study, dashes this notion. Double hits are the bane of swordplay, and it is difficult to eradicate them entirely in both play and competition. And, given the large number of accounts of duels in which both antagonists were wounded in contre-temps or “exchanged thrusts,” it was clearly a problem in actual combat as well.

“It is a prejudice to think that swordsmanship is meant solely to slash an opponent. It is meant not to slash an opponent, but to kill evil. It is a way of allowing ten thousand men to live by killing a single evil man.”

—From the Heiho Kaden Sho (Family-Transmitted Book on Swordsmanship), seventeenth century, translated by Hiroaki Sato, 1985.

“The accomplished man does not kill people by using his sword; he lets them live by using his sword.”

—From Taia Ki (On the T’ai-a), seventeenth century, translated by Hiroaki Sato, 1985.

Courtesies

Far more courtesies and expectations of behavior than are given below may be found here: Fencing Salles & Fencing Commandments.

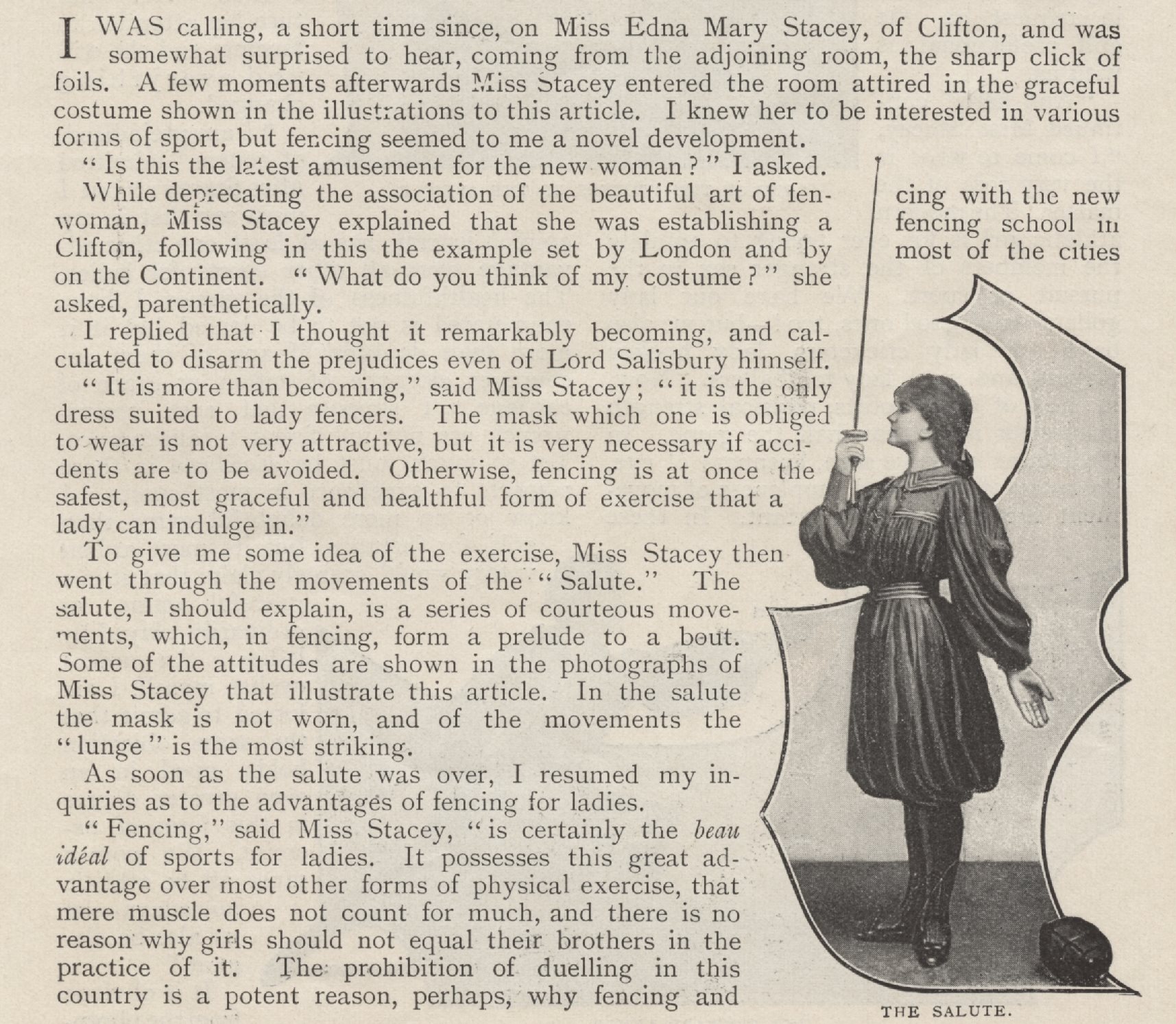

“The salute is an usage established in all the fencing schools, in order to preserve the politeness that we owe to one another.”

—J. Olivier, Fencing Familiarized /L’Art des Armes Simplifié, 1771. Note the phrase in all the fencing schools; the salute was generally not used in a duel or rencontre, at least not among the French and their disciples.

“It is a polite custom to salute your opponent with your blade before the bout, and to offer him your hand at the end.”

“Once the fencer has taken the guard position, he must be considerate of his opponent. Neither fencer must talk during the bout. Fencing requires the greatest possible attention, and this may not be diverted in any way or for any reason except by fencing tactics.”

“In fencing against an opponent who acknowledges your superiority, sportsmanship demands that you do not make the most of your advantages; rather should you assist his swordplay as much as possible, and avoid placing him in a painful or ridiculous position by over-emphasizing your superiority.”

—Luigi Barbasetti, The Art of the Foil, 1932

Note the phrase, “acknowledges your superiority.” You may in all honor and good form make the most of your advantages against a fencer who does not acknowledge your superior skill.

“Don’t show any sign of bad temper if you are the loser.”

“Don’t get conceited, or be haughty, if you are the winner.”

“Don’t forget always to be modest and courteous.”

“If your adversary should prove far superior to you, do not show discontent or bad temper; do not be disheartened, keep up your style and do your best, no matter how badly you may be beaten. Take your defeat in the right spirit, it will help to improve you; take it as a lesson you needed. Remain always the ‘correct gentleman.'”

“Not shaking hands with an adversary after a match or a rencontre is a great lack of courtesy, and should be reprimanded. Saluting an adversary previously to the beginning of a bout should be done before placing the mask on the head.”

—Félix Gravé, Fencing Comprehensive, 1934

“Une simple observation pour terminer: à l’épée comme au fleuret, le silence est de rigueur. La parole est aux armes, dit-on; c’est-à-dire que, seules, la tête el la main doivent agir.”

“A simple observation to end with: at epee as at foil, silence is mandatory. One lets the weapons speak; that is to say, the head and hand must act alone.”

—Claude La Marche [Georges-Marie Félizet], Traité de l’épée, 1884.

“No Scholar nor Spectator without a licence from the Master, should offer to direct or give advice to any of the Scholars, who are either taking a Lesson or Assaulting…First, because without permission they take upon them to play the Master; And secondly, because they reprove oft-times their Commerads for the same very fault they themselves are most guilty of, although perhaps not sensible of, which when By-standers perceive, they smile at them (and with just reason) as being both ignorant and impertinent; therefore it would be a great deal more commendable in them, to be more careful in rectifying their own faults, and less strict in censuring others.”

—Sir William Hope, The Fencing Master’s Advice to His Scholar, 1692

“Upon their first appearance upon the Stage, they march towards one another, with a slow majestick pace, and a bold commanding look, as if they meant both to conquer; and coming near together, they shake hands, and embrace one another, with a chearful look. But their retreat is much quicker than their advance, and, being at first distance, change their countenance, and put themselves into their posture; and so after a pass or two, retire, and then to’t again: And when they have done their play, they embrace, shake hands, and putting on their smoother countenances, give their respects to their Master, and so go off.”

—Richard Ligon, A True and Exact History of the Island of Barbados, 1673. Ligon is describing Portuguese African slaves brought to Barbados, who are fencing expertly with single rapier and rapier and dagger in the manner of Jeronimo Sanchez de Carranza. But for the respects to their “Master”–their owner–the description is a perfect one of how fencers should comport themselves during a bout, from beginning to end.

On Becoming a Fencer

“The way is in training.”

“The essence of this book is that you must train day and night in order to make quick decisions. In strategy it is necessary to treat training as a part of normal life with your spirit unchanging.”

—Musashi Miyamoto, Go Rin No Sho (A Book of Five Rings), 1645.

“For Fencing is an Art which depends mainly upon Practice, and who ever thinks to acquire it any other way, is I assure him mightily mistaken, and the more a man practice and with the more different humors, so much the better for him…”

“[S]o that let the greatest Artist in the World forbear but the Practice of it [fencing] for a twelve month, although I confess he can never loss [lose] the Judgement he hath acquired, yet he will certainly when he cometh to practice again, find his Body and Limbs stiffer, and his Hand and motions both for Defence and Offence, neither so exact, nor by far so swift, as if he had been in a continual Practice, I mean at least once a Week or Fortnight…”

“[T]here is as much difference betwixt taking a Lesson, or playing upon a Masters breast, and Assaulting or performing the same Lessons upon your Commerads, as there is betwixt the repeating of an eloquent Discourse already penned, and the composing of one.”

—Sir William Hope, The Fencing Master’s Advice to His Scholar, 1692

“Finally, Practice is the Marrow and Quintessence of the Art, for without that, a Papist may soon forget his Pater-noster; but by frequent Practice, a Man gains much experience daily, and is continually improving his Skill. This being the last Observation, and one of the chief, no Opportunities of Practising ought to be neglected.”

—Zachary Wylde, The English Master of Defence, 1711

“This being done, place yourself on the position of the guard, with a graceful, but unaffected appearance, animated with a brave boldness; for nothing requires a man to exert himself more than sword-defence, and it is as difficult to attain such an air of intrepidity without much practice, as it is difficult to become perfectly expert in the art.”

—Joseph Roland, The Amateur of Fencing, 1809.

“Si vous voulez devenir un véritable tireur, certainement il vous faudra de longues années de travaux, de méditations sévères, d’exercices incessants.”

“If you would be an accomplished swordsman, you will certainly require years of hard work, close application, and incessant practice.”

—César de Bazancourt, Les Secrets de l’Épée, 1862. The translation is from the English edition, Secrets of the Sword, 1900, translated by C. F. Clay.

And yet, reality too often sets in, past and present:

“Souldiers in a Battel or Attack, do not regularly alwayes observe this [correct] Method [of swordplay]: and most part thrust on any way, without troubling themselves much with the Tierce, Guart, or Feint; but make use of their Swords to attack or defend themselves, according to the small talent that God Almighty has given them.”

—Louis de Gaya, A Treatise of the Arms and Engines of War, 1678

“It was soon over. The brute strength, upon which Levasseur so confidently counted, could avail nothing against the Irishman’s practiced skill.”

—Rafael Sabatini, Captain Blood, 1922

“…and that, too confident of himself, he had neglected to preserve his speed in the only way in which a swordsman may preserve it.”

—Rafael Sabatini, The Black Swan, 1932

“[A] man can never be called a compleat Sword Man, untill he can Defend himself with all kindes of Swords, against all sorts his Adversary can choose against him.”

—Sir William Hope, The Compleat Fencing-Master, 1710.

“L’escrime est une maîtresse capricious et frivole; elle résiste longtemps à ses adorateurs, mais, à ceux qui ont su la posséder, elle reserve des joies incomparables.”

“Fencing is a capricious and frivolous mistress; she long resists her suitors, but, to those are able to possess her, she reserves incomparable joys.”

—Dr. Achille Edom, L’Escrime, le Duel & l’Épée, 1908. My translation.

“For double hits are misfortunes, verging on crimes, and it is not in the lesson, but in friendly looseplay that one must learn to avoid them; or at least not be to blame when they occur.”

“One wastes one’s time and opportunity in going fast with them and piling up a score of hits. If one resolves to give only hit for hit, but to be careful that all the hits one gives have been worked for with due preparation, the bout with the less expert can be very fruitful indeed.”

—Percy E. Nobbs, Fencing Tactics, 1936.

“Another advantage which single-stick possesses is that you may learn to play fairly well even if you take it up as late in life as at five and twenty; whereas I understand that, though many of my fencing friends were introduced to the foil almost as soon as to the corrective birch, and though their heads are now growing grey, they still consider themselves mere tyros in their art.”

—R. G. Allanson-Winn, Broadsword and Singlestick, 1911

“Look at what a lot of things there are to learn—pure science, the only purity there is. You can learn astronomy in a lifetime, natural history in three, literature in six. And then, after you have exhausted a milliard lifetimes in biology and medicine and theocriticism and geography and history and economics—why, you can start to make a cartwheel out of the appropriate wood, or spend fifty years learning to begin to learn to beat your adversary at fencing. After that you can start again on mathematics, until it is time to learn to plough.”

—Merlin speaking to Wart, in T.H. White’s The Once and Future King, 1958

“The more you understand fencing, the more you will enjoy it. This particularly applies to the novice for, like all highly skilled games, it is easy to be put off by the chore of having to begin right at the beginning.”

—Bob Anderson, All About Fencing, 1963. Mr. Anderson was a British Olympic fencer and Olympic coach who became Hollywood’s leading swordplay choreographer, following in the footsteps of Fred Cavens and Ralph Faulkner. The fencing in Star Wars, The Princess Bride, and Alatriste are but three of his many film works. He died in January, 2012, and was inexplicably and inexcusably left out of the In Memoriam tributes at the 2012 and 2013 Oscars.

“The next exercise that a young man shall learn, but not before he is eleven or twelve years age, is fencing…”

—Lord Herbert of Cherbury, 1624, quoted in J. D. Aylward, The English Master of Arms, 1956. The stated age at which to begin fencing is valid today. Although children can be taught earlier, it should be done as fun physical preparation for learning to fence, not instruction in fencing itself with the goal of competition. Unfortunately, youth fencing, often beginning as young as six years (or even younger!), is modern fencing’s cash cow; it pays the bills, and as such children are pushed into competition before they’re physically or psychologically prepared, leading to burn out. Over-pressured by parents living vicariously through their children and coaches looking for “champions,” they lose their love for swordplay or never come to love it at all.

“[G]enerally speaking, few persons, except those of liberal education, ever think of, much less learn, the Art of Fencing, and they, of course, are understood to be familiar with the French language.”

—Joseph Roland, The Amateur of Fencing, 1809

“To be in possession of what you know, you must be in possession of yourself.”

—le sieur Labat, L’art en fait d’armes, 1696, from Mahon’s translation entitled The Art of Fencing, 1734

“For, Anthony, he that would be a true sword-master must first be master of himself, then of his blade, so shall he be master of his adversary. You follow me, I hope?”

—Jeffery Farnol, Adam Penfeather, Buccaneer, 1940

“Well, a man is as he is trained.”

—Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, Micah Clarke, 1894

“Fencing, like other sciences, cannot be degraded to a mechanical art, that may be infallibly practiced by a receipt; nor can it be thoroughly and completely acquired by only reading a book on the subject.”

“At the same time, I earnestly caution the intelligent young amateur, before he adopts any of these new methods of executing the different movements, &c. in Fencing, to submit them to the test of the strictest examination, and to determine, if possible, how far they appear to be consistent with reason and practicability.”

“[T]he pupil, who I wish at all times to make use, but not too hastily, and without partiality, of his own judgement, and not upon every occasion to take for certain evidence any proposition upon the authority alone of a master, merely because he is a master, or that the same may be found in print.”

“They are shown both methods, and after a proper demonstration of their respective merits, I always leave it to their own judgment, to practise that which they find by experience to succeed best. It is on this principle alone I wish all my observations to be weighed. I detest the maxim of acting upon mere authority, without any convincing proof.”

—Joseph Roland, The Amateur of Fencing, 1809

“This is what made him a great coach: he taught strategy and tactics, not just attacks and parries. He taught you how to analyze your opponents, get inside their heads, figure out what they would do, what were their strengths and weaknesses. He taught you to have confidence in yourself, to work hard, to settle for nothing less than the best you could do. He knew how to coax, insult, and inspire his students to achieve ever greater heights of success.”

—Roger Jones, describing Lajos Csiszar in an article, 2000. Csiszar was one of Italo Santelli’s three protégés, and coached Dr. Eugene Hamori after he defected to the US during the 1956 Olympic Games (and after the Hungarian saber team won gold). From an article by Roger Jones, 2000. Jones was one of Csiszar’s US students as well as a member of the 1955 and 1957 US epee teams, an alternate to the 1956 Olympic team, a longtime AFLA/USFA/FIE official, a strong vocal opponent of gamesmanship and cheating, and, of course, like many male students of Santelli, Szabo, Csiszar, Zold, and Hamori, a gentleman and a swordsman. A US Navy Reserve Captain, an author, and an icon of the plastics industry, he passed away in 2014. As with most of my “old school” fencing friends and acquaintances, I had great conversations with him, from which I learned much. My favorite anecdote of his concerned an international fencer who once approached him to throw a bout to him, an unfortunately common practice at the international level, so he could advance. Roger had lost too many bouts to advance. Roger was incensed by the suggestion and defeated his adversary, denying him the ability to advance and putting him in his rightful place. Csiszar was elated: “You fought for your honor!”

“While training, the pupil should naturally practice and experiment ignoring for the time being the question of his powers of hitting, so that he can constantly enrich his knowledge and skills.”

“Fencing lessons built up systematically, practice under bout-like conditions, exercises “au-mur”, conventional exercises, exercises designed to parry attacks, bouts, systematic free fencing, unlimited bouts, bouts fenced until 5 or 10 hits [and today, 15] and competitive fencing constitute the framework within which the fencer can grow to the stature of a competitor.”

—Imre Vass, Párbajtörvívás, 1965, from the first English translation, Epee Fencing, 1976

“American fencers and coaches should understand and build their program on the fact that the coach’s role is only 10 percent of the total effort. Fencers must rely on themselves in training and in competition. Coaches should not try to ‘sell’ themselves to the students. Students must become independent.”

“[Smaller competitions are] ‘practice competitions,’ where the fencer does not necessarily have to win, rather, he should use a wide variety of his moves while checking and following his progress. On major competitions, the fencer should always try to win, and go all out to win, ‘even if he only has one move…'”

—Kaj Czarnecki, American Fencing, Jan/Feb 1980. Maitre Czarnecki, who passed away in 2018, was a Finnish Olympic epee fencer and fifteen time Finnish and Scandinavian champion, winning in all three weapons. He was a leading coach in Sweden, helped train Johan Harmenberg, and eventually became one of the epee coaches at the US Modern Pentathlon Training Center at Fort Sam Houston. I heard him make similar remarks during an epee clinic at the Mardi Gras Fencing Tournament in New Orleans that spring. Too few coaches take these views today, with the result that many fencers are anything but independent on the strip or elsewhere. Many coaches prefer to have their students bound too closely to them–and to take credit for their victories, if not always their losses.

“Always combine footwork with techniques being practiced.”

“Footwork and more footwork. Speed and more speed.”

“Develop these qualities

1. Smoothness 2. Ease 3. Accuracy”

“To find stillness in movement, not stillness in stillness.”

—Bruce Lee, from his notes on “Incorporating fencing principles,” quoted from Jeet Kune Do: Bruce Lee’s Commentaries on the Martial Way, compiled and edited by John Little, 1997. Bruce Lee studied both Western boxing and Western fencing, and incorporated some of their principles in Jeet Kune Do.

“[I]n the beginner’s mind there are many possibilities, but in the expert’s there are few.”

—Shunryu Suzuki. Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind, 1970. That is, keep your mind open and don’t fall victim to your knowledge or success.

“Bonus homo semper tiro.”

“A good person is always a novice.”

—Derived from Martial XII.li.2. See Suzuki above.

The En Garde: Three Not Incompatible Opinions

“The bravest gentlemen of arms, which I have seen, were Sir Charles Candis, and the now Marquis of Newcastle, his son, Sir Kenelm Digby, and Sir Lewis Dives, whom I have seen compose their whole bodies in such a posture, that they seemed to be a fort impregnable. They were the scholars of John de Nardes of Seville in Spain, who with the dagger alone, would encounter the single rapier and worst him. This exercise is most necessary for you, and also excellent for your health.”

—William Higford, Institutions: Or, Advice to His Grandson, 1658

“This being done, place yourself on the position of the guard, with a graceful, but unaffected appearance, animated with a brave boldness…”

“In whatever attitude you may think it necessary to present yourself facing your adversary, if your mind is prepared to attack and defend, you will be, properly speaking, ‘on guard.'”

—Joseph Roland, The Amateur of Fencing, 1809

“In your en garde you must lean forward slightly and thereby appear to be always in motion, as if you are always attacking. When your opponent looks at you, he or she must believe you are constantly attacking no matter what you are doing.”

— Dr. Eugene Hamori, as best I recall, to me forty years ago, to my wife within the past five.

On Patience as a Fencing Virtue: Epeeists, Take Heed!

“’Prevail by patience,’ is the motto of my house, and I have taken it for the guiding maxim of my life.”

—de Bernis, in Rafael Sabatini’s The Black Swan, 1932. The novel builds to a duel at the climax.

Patientia vincit.

(Patience conquers, to conquer or prevail via patience.)

—Old motto and the likely Latin version of the motto of Charles de Bernis, Sabatini’s hero in The Black Swan. Used by the Huntsville Fencing Club until replaced with the motto below.

Patientia ferox vincit.

(To conquer or prevail via a fierce or warlike patience.)

—Modification of patientia vincit based on my experience fencing and teaching fencing, for the Huntsville Fencing Club and Salle de Bernis, 2012

“Patience need not be passive!”

—To my fencing students, circa 2005 to the present.

“L’assaut en un coup demande de la prudence, mais non de l’inactivité.”

“An assault for one touch demands prudence, but not inactivity.”

—J. Joseph Renaud in L’Escrime: fleuret, par Kirchoffer; épée, par J. Joseph Renaud; sabre, par Léon Lécuyer, 1913. Compare with Patientia Ferox Vincit and “Patience need not be passive!” above. I discovered this quote in April 2013, proving, yet again, that there is little original in fencing, and none of us are as original as we think we might be.

“Errors of distance, overeagerness, foolhardiness and impatience, are faults for which every épéeist of experience is on the look-out in his opponent’s game. More, they are faults which the épéeist will try to bring about in the unwary swordsman.”

—Roger Crosnier, Fencing with the Epee, 1958. As or more important, in my opinion, than watching for or inducing these errors in the opponent, is preventing them in oneself.

“Patience is the first virtue of an épée fencer.”

—Luigi Barbasetti, The Art of the Sabre and the Épée, 1936

Notwithstanding the necessity of aggressive patience in epee, or in any dueling sword, with the introduction of a severe modern “non-combativity” rule that forces epeeists to fence aggressively–put simply, there must be a touch scored within a minute or there is a penalty–, the often foolish and feckless fencing powers-that-be are undermining the very essence of swordplay itself. Action in fencing is not composed of touches but of physical and intellectual maneuvering. Some of the most exciting bouts I’ve ever fenced or watched have had few touches scored. My wife and I often go eight or more minutes without a touch (eleven minutes once), and an old friend of mine, a truly classical epeeist, and I often go several minutes without a touch–and in both of these examples other fencers typically stop to watch. A lack of prodigious scoring doesn’t equate with spectator boredom. If it did, no one would watch baseball or soccer, or for that matter, golf. Why the rule change? It’s pressure from the IOC: if sports don’t draw enough spectators (i.e. advertising dollars), they’re out. Fencing officials, elite coaches, and elite fencers are abandoning fencing’s core values for the sake of the cachet of the Olympic Games, which in fact field only a small number of fencers as compared to the World Championships.

“A l’épée, il faut savoir attendre.”

“In epee, one must know how to wait.”

—Claude La Marche [Georges-Marie Félizet], Traité de l’épée, 1884. The translation is by Brian House from his excellent English version, The Dueling Sword, 2009

And yet…

“Never hesitate!”

—Dr. Francis Zold, personal communication during a lesson, 1978

Fencing Qualities, Techniques, & Tactics

“La fortune aidait souvent la valeur un peu téméraire.”

“Fortune often aids valor that is a bit reckless.”

—Capt. René Duguay-Trouin, Mémoires, 1741. Duguay-Trouin was a famous late 17th and early 18th century French privateer and naval officer who once captured a ship by boarding it, then engaging the enemy captain single-handedly, sword-in-hand, forcing him to surrender in the style of the great Hollywood swashbucklers. He was a duelist (bretteur) when young, and later brought at least one fencing teacher (a master’s assistant) aboard his ship in order to improve his crews’ fighting ability. He later had a rencontre in the street with the fencing teacher, a fight that was anything but academic. The quotation may derive from audentis fortuna iuvat, later written by Virgil as audaces Fortuna iuvat (Fortune aids the bold). Similar is the SAS motto, ‘Who Dares Wins.'” My translation.

“Dans le noble exercice des armes, ce n’est pas aux audacieux que sourit la fortune, mais aux persévérants.”

“In the noble exercise of arms, it is not the audacious that Fortune smiles upon, but on those who persevere.”

—Anthime Spinnewyn, L’Escrime à l’épée, 1898. My translation. Compare with Duguay-Trouin above, and with the admonitions of Francis Zold and Nobuo Hayashi below.

“Joignez dans le combat, la valeur à la prudence, la peau du Lion à celle du Renard.”

“In battle let valour and prudence go together, the lyon’s courage with the fox’s craft.”

—le sieur Labat, L’art des armes, 1696. The English is from Andrew Mahon’s translation, The Art of Fencing, 1734.

“The man in the periwig, whose every movement was as swift and light-footed as a cat’s, lowered the sword point.”

—John Dickson Carr, The Devil in Velvet, 1951

“Fencing without Judgement, is just like a Watch without a Spring, a Neat piece of Work with a great many fine Wheels, but without any Motion, the want of which maketh her useless.”

—Sir William Hope, The Sword-Man’s Vade-Mecum, 1694

“[T]he true Art of Sword-defence depends, in great measure, on judgement in deceiving the adversary’s motions, and in not being deceived by his.”

—Joseph Roland, The Amateur of Fencing, 1809

“For what are all strategems, ambuscades, and outfalls but lying upon a large scale?”

—Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, Micah Clarke, 1894

“Perhaps it would not be an exaggeration to say that the fencer’s skill in tactics is displayed to a large degree by the ability to mislead an opponent, to recognise the opponent’s intentions and to discern any attempts to be mislead.”

—Zbigniew Czajkowski, “Fencing Actions—Terminology, Their Classification and Application in Competition,” n.d.

“Double-dealing is the basis of swordsmanship. By double-dealing, I mean the stratagem of obtaining truth through deception.”

—From The Death-Dealing Blade, Yagyu Munenori, 17th century, translated by Hiroaki Sato.

“A duel, whether regarded as a ceremony in the cult of honor, or even when reduced in its moral essence to a form of manly sport, demands a perfect singleness of intention, a homicidal austerity of mood.”

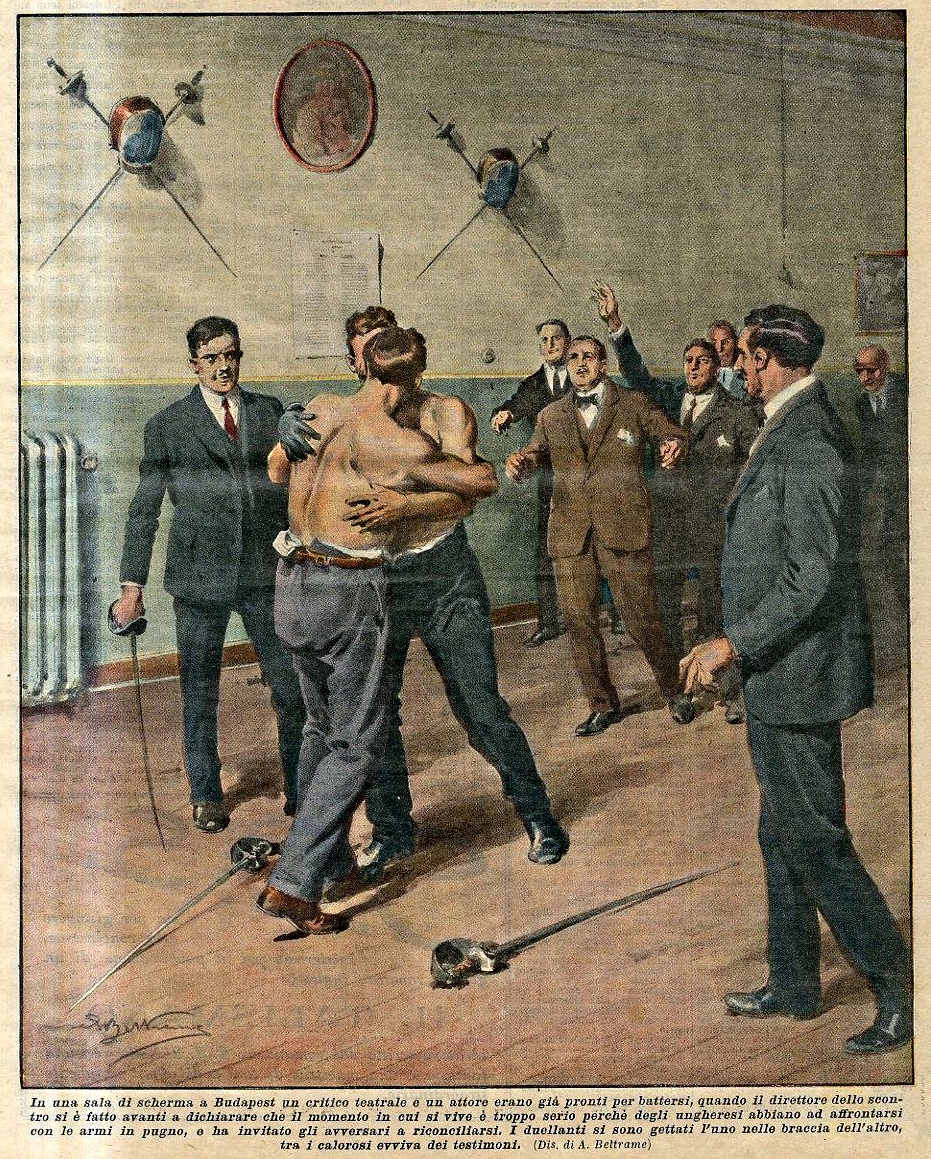

—Joseph Conrad, The Duel, 1908. Conrad’s story was based on the actual tale of a long-running series of duels between two Napoleonic officers. It was later made into an excellent film, The Duellists, 1977.

“Be simple, be smart. Don’t move your weapon until you are ready to use it… then SHOOT! Let the younger fencers become eager and make mistakes. Against the older ones, use your speed and strength. Remember, mano de ferro, braccio di gomma—have a hand of iron and an arm of rubber.”

—Italo Santelli, quoted by Lajos Csiszar quoted by Roger Jones, [1950s] 2000.

“Always keep a Spring in our Arm and Wrist, to make your Thrust go the quicker, and your Parie the more sure, and as soon as you have done either, Recover them again.”

—Donald McBane, Expert Sword-man’s Companion, 1728.

Ratón que se sábe mas de un horádo, présto le cagé el gáto.

The cat soon catches the rat that knows but one hole. [More literally: the mouse who knows more than one hole soon escapes the cat.]

—proverb quoted in John Stevens, A New Spanish Grammar, 1725

“Rouse me not.”

—The Conisby family motto, from Jeffery Farnol’s swashbuckler Martin Conisby’s Vengeance, 1921. Some fencers, myself included, fence well when “roused” or angered, at least for a while, although historical the usual advice has been to keep one’s anger and temper reined in. If one is to fence angry or in fury, let it be cold-blooded rather than hot-blooded. See also Dr. Eugene Hamori’s advice to me below.

“One last bit of advice for the strip: Get MAD at your opponents, at the director, at the world, etc., when you fence and quit apologizing for yourself.”

“But if it works for you, then do it.”

—Dr. Eugene Hamori, personal correspondence, 1995

Anger is not recommended for hot-tempered fencers, but for cold-blooded ones who can focus their anger–and it won’t last forever, this focused anger. You’ll still have to rely on cool-headed technique most of the time.

“Your opponent, when struck, is bound to transform himself. When struck, he thinks, ‘What’s this! I’ve been struck!’ and may get angry. If he gets angry, he becomes resolute. If you relax at that moment, your opponent will strike you down. Regard the opponent you’ve struck as a furious boar.'”

—From The Life-Giving Sword, Yagyu Munenori, 17th century, translated by Hiroaki Sato. I’ve warned cocky fencing students not to anger they’re opponents unless they know beforehand that the opponents will lose control. Many, as noted above, will not. It’s a fine lesson for a cocky student to be soundly beaten by an adversary he or she has angered.

“And, remember, there is nothing bad in fencing, provided that it succeeds.”

—Sir Richard Burton, The Sentiment of the Sword, 1911. See also Eugene Hamori above. It should be noted that Burton is, in the case of salle fencing and dueling, speaking only of honorable fencing, certainly not the gamesmanship and “cheating within the rules” far too many fencers, albeit a minority thankfully, consider fair play.

“[The epee or duelling sword] is a democratic weapon in that the less skillful fencer always has a chance to win; but it is an exacting task for a fencer consistently to achieve distinction in duelling sword unless he combines a fundamentally sound technique with the instinct of strategy.”

—Julio Martinez Castello, The Theory and Practice of Fencing, 1933. The same may be said of the smallsword or any dueling sword.

“Épée fencing requires a special technique, courage, opportunism and concentration of effort in the highest degree. It is the highest expression of the art of fencing, because it alone is based on the conception of hitting the opponent without oneself being hit… Litheness, agility and speed, which are the essentials for the successful épéeist, are largely based on his footwork… Épée fencing is par excellence a game of timing, tactics and bluff… Subtlety, bluff and courage are salient features of this game… While caution is essential with the duelling weapon, the best devised moves will come to naught unless the épéeist possesses courage to risk everything when the right opportunity presents itself.”

—C-L de Beaumont, OBE, in Fencing: Ancient Art and Modern Sport, 1960

“There is in steel a subtle magnetism which is the index of one’s antagonist.”

—Rafael Sabatini, The Suitors of Yvonne, 1902

“Here was a man whom much and constant practice had given extraordinary speed and a technique that was almost perfect. In addition, he enjoyed over André-Louis physical advantages of strength and length of reach, which rendered him altogether formidable. And he was cool, too; cool and self-contained; fearless and purposeful. Would anything shake that calm, wondered André-Louis.”

—Rafael Sabatini, Scaramouche, 1921

“NOVEL: Pshaw! Talking is like Fencing, the quicker the better; run ‘em down, run ‘em down; no matter for parrying; push on still, sa, sa, sa: no matter whether you argue in form, push in guard, or no.

MANLY: Or hit, or no; I think thou alwayes talk’st without thinking, Novel.”

—William Wycherley, The Plain-Dealer, 1674. The lines are satire. Captain Manly is an honest plain-speaking fighting seaman who serves “out of Honour, not Interest,” while Novel is “a pert railing Coxcomb,” or in other words, an ass, and clearly no swordsman either.

“Be not over elated at the thrusts you hit with, nor despise those by which you are hit.”

“Never set any value upon any thrust you give, before you examine whether it was well given, without any danger attending it.”

“Study the danger and advantage of every thrust you make.”

—Andrew Lonnergan, The Fencer’s Guide, 1771.

“We consider being in tune bad, being out of tune good. When you and your opponent are in tune with each other, he can use his sword better; when you are not, he can’t. You must strike in such a way as to make it hard for your opponent to use his sword well… The point is to stay out of tune with your opponent. Out of tune, you can step in.”

—From The Death-Dealing Blade, Yagyu Munenori, 17th century, translated by Hiroaki Sato. In other words, don’t match your opponent’s rhythm. And if you do, you must be prepared to strike just before your opponent intends to strike, breaking tempo in this manner. This principle–“Fence out of tune!” is one I constantly instill in students’ practice.

“C’est une chose si difficile à prendre que lest temps, l’épée à la main, que je ne conseille a personne de s’y trop hasarder.”

“Taking tempo is such a difficult thing to do, sword-in-hand [i.e. with a real sword], that I do not recommend anyone risk it too much.”

—André Wernesson, sieur de Liancour, Le maistre d’armes: ou, L’exercice de l’epée seule, dans sa perfection, 1686. My translation.

Such tempo actions, seldom recommended by duelists, make up much of modern epee. My first fencing master, who had fought at least one duel, once pointed out to me the dangers of tempo actions with real swords, particularly in counter-attacks: they will not stop fully developed attacks. Even a time thrust to body might stop the forward motion of an attack only if it strikes the breastbone, base of the ulna, or possibly forehead, targets to small to risk. The danger is even greater with counter-attacks to the arm when the adversary has launched a strong attack. Nonetheless, even in the 17th and 18th centuries, many swordsmen used time hits in combat with sharps. See immediately below, and also all quotes by Sir Wm. Hope and Donald McBane.

“I bound his Sword and made a half Thrust at his Breast, he Timed me and wounded me in the Mouth; we took another turn, I took a little better care, and gave him a Thrust in the Body…”

Donald McBane, Expert Sword-man’s Companion, 1728. Time thrusts, in this case a disengage from a bind, when used wisely in this era were made in opposition and typically with the unarmed hand closing the line as well, in order to ensure maximum safety. Mouth wound notwithstanding, McBane killed his adversary, a boastful Gascon. As noted elsewhere, time hits were common in duels and affrays in spite of cautions regarding their use in combat.

“This last fault of drawing back the hand on the attack, or in plain terms, stabbing, deserves a word by itself. It is perfectly fatal to good fencing…Before delivering his point, the stabber checks the onward movement of the blade by drawing back the hand, and therefore loses all the space and time wasted in first withdrawing the hand from the starting-point and then returning to it. While this process is going on, all the opponent has to do is to straighten, which is clearly quicker, as it is all on the way. No sane man would dream of laying himself open in such a way if he were engaged in fighting for his life…”

—Henry Arthur Colmore Dunn, Fencing, 1899. Unfortunately, this technique of “stabbing” (i.e. “bent arm attacks” or “attacks in invitation”) and the dangers it holds to the user were swords real, is now considered an acceptable form of attack—in fact, it is the most common—in modern foil and saber fencing, to the point [pun half-intended] that neither weapon much resembles actual combat anymore, but are more akin to a game of tag with steel rods, all governed by a set of esoteric rules pandering to an imaginary audience.

“The flexibility of the foil will enable an expert fencer to produce effects that may dazzle the uninitiated, while they are well understood, and known to be mere sleight-of-hand tricks by those familiar with the exercise… If an expert fencer makes a rapid pass over his opponent’s guard, striking his foil near its centre, with force, against that of his opponent, he can spring the point of his foil from ten to eighteen inches, according to the flexibility of his blade; whereas if he makes a cut with a sword, using equal force and striking with the edge of his blade, he can not spring the point of his weapon the hundredth part of an inch.”

—Matthew J. O’Rourke, A New System of Sword Exercise, 1872

In other words—take note, those of you who belong to the significant sub-set of classical fencers whose understanding of fencing history is often of the cherry-picked and ideologically fanciful variety—the flick has been around a long time. For good reason did foilists in the 19th century, and even into the early 20th, wear fat fencing gloves thickly padded with horsehair. In fact, it’s impossible to entirely get rid of the flick, given the need for practice weapons to have flexible blades. Many of the 19th century foil blades I’ve examined, including some in my collection, have ridiculously flexible blades.

I’m no fan of the flick, for it’s a purely sport technique that has no place in real combat or in swordplay intended to emulate it as much as possible. I’ve included the quote above primarily to note the failure in common knowledge of fencing history: the use of the flick in modern fencing (a bit less so in foil now but still common in epee) is often cited by “classical fencers” as a reason modern fencing is “impure.” Well, so then was 19th century French foil…

“Never give up!”

—Dr. Francis Zold, personal communication, 1977-1978. This was one of his admonitions to all of his students.

“A man never gives up! A man dies first!”

—Nobuo Hayashi, my judo and jiujutsu teacher, 1979 or 1980. Sensei Hayashi was brought up before and during WWII in the old jiujutsu, had trained to become a Kamikaze pilot, and won the Japanese university judo championship in the late 1950s. His anecdotes, like those of my fencing masters, were delightful. He shouted this comment after a student, attempting to escape him on the mat, simply gave up. As I recall, Sensei Hayashi also ordered the student to leave the dojo/gym. It was in fact largely impossible for his students to escape him on the mat, although he would permit it on occasion if a technique were impeccably executed, at least by some of his more advanced students. By accident and his inattention I once slipped loose and almost escaped: he laughed, hauled me back, and twisted me into a pretzel. He had great regard for fencers and swordplay, both Japanese and European, and, seeing me under the tutelage of my fencing master one afternoon, I think he was thereby inclined afterward to indulge my learning in perhaps a paternal fashion.

Of Honor

“Ne tirez l’épée que pour servir le Prince , conserver vôtre honneur ou défendre vôtre vie.”

“Draw not your sword, but to serve your king, preserve your honor, or defend your life.”

—le sieur Labat, L’art des armes, 1696, from Andrew Mahon’s translation, The Art of Fencing, 1734

“Never lose on purpose, you must always fence to win for your honor!”

—Lajos Csiszar, quoted by student Roger Jones, 2000. The quote dates to the 1950s, and probably earlier.

“To paraphrase Theodore Roosevelt, ‘the things that will destroy American fencing are victories at any price, prestige at any price, expenses first instead of honor first, and love of subsidies and the state-supported athlete theory of ‘amateur sports.'”

—Roger Jones, “Poor Technique?” in American Fencing, March 1966

Given the current state of USA Fencing, it’s quite clear that the future Roger Jones feared has come to pass. Roger was on the US Epee Team in 1955 and was an alternate in 1956, and was also a member of the US and FIE Rules Committees. He believed foremost in honor in fencing. Full disclosure: Roger was a friend of mine, whom I first met when he contacted me while writing a review of one of my books for Naval History Magazine as I recall (Roger was also a retired reservist US Navy Captain). It became quickly apparent when the subject passed to fencing — he’d read my letters to American Fencing magazine in which I deplored the recommendation of gamesmanship, or “cheating within the rules” as he termed it — that our views were similar, and for a reason: Italo Santelli was one of our fencing grandfathers and we’d both been trained by masters descended from Santelli. In fact, Roger had trained under Lajos Csiszar at the same time as my second master, Dr. Eugene Hamori. See also the Roger Jones quotes above.

“It is happily true that in England we no longer curb the indiscreet utterance of undisciplined lips with cold steel, nor adopt the crude method of letting in light upon the mind through a hole in the body.”

—Henry Arthur Colmore Dunn, Fencing, 1899

“So in their own sense Duelling cannot properly vindicat[e] any opprobrious epithet, but that of a Coward.”

—Wm. Anstruther, Essays, Moral and Divine, 1701

“I mention these to caution you on all occasions to be on your Guard, and not to trust any man whatever who is your adversary. For many have been deceived by not taking care of themselves in these cases, tho’ their adversaries have been men of strict honour, as they thought, and that they would not be so base and villainous as to be guilty of any thing below the character of Brave Men and Gentlemen. Experientiæ Docet.”

—Donald McBane, Expert Sword-man’s Companion, 1728. McBane, a Scot, was a veteran soldier wounded several times in action, as well as a swordsman, duelist, fencing master, occasional pimp, and prize fighter. He is also the man for whom “Soldier’s Leap” is named in Scotland. Good advice not only for a duel, but for life in general. Experientiæ Docet is an abbreviated form of Experientiæ Docet Stultos: Experience Teaches Fools. McBane appears to be making a subtle joke at his own expense.

“The honor of some adversaries can never be relied on safely. In a selfish or revengeful spirit, many persons might be disposed to commit assassination, for which reason, friends and time are always indispensable.”

“No boast, threat, trick, or stratagem, which may wound the feelings, or lessen the equality of the combatants, should ever enter into the contemplation of a gentleman.”

—Joseph Hamilton, The Approved Guide Through All the Stages of a Quarrel, 1829. The first quotation is in the vein of McBane, above. Many have honor in the mundane, when there is little risk to life, limb, property, money, or reputation; far fewer have honor where there is much risk or peril.

“Eh bien! les duellistes poitevins qui ont laissé à bon titre le renom d’adversaires dangereux, Bourbeau (un cousin de l’ancien ministre), Lemaire, le fameux de Pindray — jen passe — n’étaient pas classés parmi les forts tireurs. Je le tiens de mon vieux professeur, le père Nerrière, un maître de l’école de Lafaugère que M. Legouvé a peut-être connu et qui m’a répété plus d’une fois que de Pindray, redoutable, terrible sur le terrain, n’avait travaillé sérieusèment à la salle qu’après ses duels les plus retentissants.”

“Well! The duelists of Poitou who have left good title to being renowned as dangerous adversaries, Bourbeau (a cousin of the former minister), Lemaire, the famous de Pindray—I pass over others—were not classified among the strongest fencers. I learned from my old professor, Nerrière the father, a master of the school of Lafaugère that Mr. Legouvé has perhaps known and who told me more than once that de Pindray, deadly, terrible on the field of honor, trained seriously in the salle only after he had fought his most sensational duels.”

—Arthur Ranc, in the preface to Jules Jacob’s Le jeu de l’épée, revised by Émile André, 1887.

In other words, the best sport fencers did not usually make the best duelists. See also the quote below.

“I mention this affair to show that something more than skill is necessary when using a naked weapon or shotted pistol; and the most able fencer and the first-rate shot are not always the best men in the field.”

—Andrew Steinmetz, The Romance of Duelling, 1868.

“To avoid those Desperate Combats, my Advice is for all Gentlemen, to take a hearty Cup, and to Drink Friends to avoid Trouble.”

—Donald McBane, The Expert Sword-Man’s Companion, 1728. Again, good advice in general.

More From the Latin

Praemonitus praemunitus.

Forwarned is forearmed.

—quoted in Captain Blood: His Odyssey by Rafael Sabatini

Occasionem cognosce.

Recognize an opportunity.

Quaere verum.

Seek the truth.

Festina lente.

Make haste slowly.

Aut inveniam viam aut faciam.

Either I shall find a way or I shall make one.

Pen & Sword

“Pour un oui, pour un non, se battre, —ou faire un vers!”

“For a yes, for a no, to fight, —or write a verse!”

—Edmund Rostand, Cyrano de Bergerac, 1897.

“La plume s’associe fréquemment á l’épée…C’est que la littérature est une escrime intellectuelle et la polémique, á plus forte raison: arguments et objections y cliquettent autant que lames d’acier.“

“The pen is frequently associated with the sword…This is because literature is an intellectual fencing and controversy, even more so: arguments and objections click and clatter as much as steel blades.”

—Emma Lambotte, L’Escrimeuse, 1937. Mme. Lambotte was a noted Belgian poet and the muse and patron of painter James Ensor—and a fencer as well.

“Le fleuret, c’est la grammaire; l’épée c’est l’éloquence. Racine et Boileau écrivaient au fleuret; Shakespeare et Victor Hugo — à l’épée.”

“The foil is grammar; the epee is eloquence. Racine and Boileau wrote with the foil; Shakespeare and Victor Hugo — with the epee.”

—Aurélien Scholl, in the preface to Deux Écoles d’armes: L’escrime et le duel en Italie et en France by Daniel Cloutier, 1896. My translation. Today we might amend this to say “classical foil is grammar,” modern foil having departed, several decades ago, far from the rigor and conventions of classical foil.

“Tomando ora la espada, ora la pluma.”

“Now taking up the sword, now the pen.”

—Garcilaso de la Vega, Égloga III (v.40), early 16th century. Garcilaso was a 16th century Spanish soldier-poet and true Renaissance man. He died in 1536 of wounds suffered in battle at Le Muy, France. Armas y lettras—arms and letters—is a common theme in 16th and 17th century Spanish literature.

“Nunca la lanza embotó la pluma ni la pluma la lanza.”

“The lance never blunted the pen nor the pen the lance.”

—Sancho Panza in Don Quixote by Miguel de Cervantes

“I’ll make thee glorious by my pen,

and famous by my sword;”

—James Graham, Marquis of Montrose, “I’ll never love Thee more,” 1642 or 1643. Sir Walter Scott reversed glorious and famous, apparently not appreciating the attachment of glory to the pen. Montrose, a Scottish hero, led a guerrilla campaign through the Highlands against Cromwell’s forces. In the end he was hanged, instead of being beheaded as was due given his rank. His body was decapitated after his death, and his head was piked at the Tollbooth in Edinburgh.

To the Reader.

Harke, Reader, would’st be learn’d ith’ Warres,

A Captaine in a gowne?

Strike a league with Bookes and Starres,

And weave of both the Crowne?

Would’st be a Wonder? Such a one

As would winne with a Looke?

A Schollar in a Garrison?

And conquer by the Booke?

Take then this Mathematick Shield,

And henceforth by its Rules,

Be able to dispute ith Field,

And combate in the Schooles.

Whil’st peacefull Learning once agen

And th’ Souldier do concorde,

As that he fights now with her Penne,

And shes writes with his Sword.

RICH LOVELACE

A. Glouces. Oxon.

—Richard Lovelace, the famous cavalier poet, in the preface to Pallas Armata: The Gentlemen’s Armorie by G. A. (probably Gideon Ashwell according to sword scholar J. D. Aylward), 1639

“…the penny siller [silver] slew mair souls than the naked sword slew bodies.”

—Sir Walter Scott, Rob Roy, 1818. Not the pen, but something like it in that it can be used for both good and evil.

“[H]ow much more cruel the pen may be than the sword.”

—Robert Burton, The Anatomy of Melancholy, 1621

“Benbu itchi.”

“Pen and sword in accord.”

—Japanese, 17th century or earlier.

Fencing Language

“Hé là!”

—Literally, “Hey there!” Often shouted during a vigorous exchange ending in a successful touch, or at least it once was until recently. More embarrassingly, it is sometimes shouted in expectation of a touch that ultimately fails. In Cyrano de Bergerac is the shout “Hé! Là donc!”—that is, “Hey! There thus!” Many old French masters and fencers believed in absolute silence during swordplay, while many Italians permitted some expressions. An occasional Hé là! or similar ejaculation is acceptable in my opinion; anything else is boorish.

“Hé là, Pamela!”